COMSAT lab developed history

Feb. 16, 2005

Susan Singer-Bart

Staff Writer

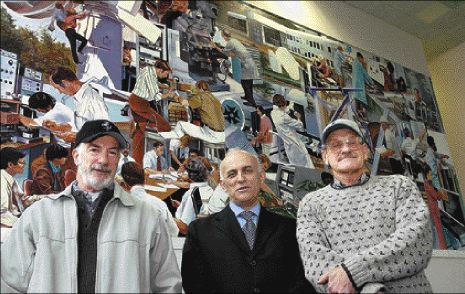

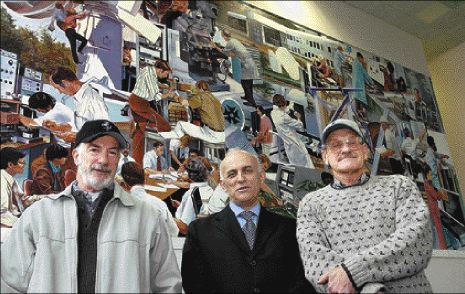

Brian Lewis/The Gazette

Former COMSAT employees (from left) Joe Molz of Sykesville, Ken Betaharon of

Rockville and Bob Gruner of Damascus in front of a mural in the lobby of the COMSAT building off Interstate-270 in Clarksburg.

The mural, painted in 1978 by Terry D. Rodgers, is a collage of candid moments depicting employees hard at work.

|

For more than 30 years the best and the brightest engineers, physicists and technicians worked at COMSAT Laboratories in

Clarksburg, creating the foundation for today's world of instant global communications.

"I call it an engineering sandbox," said Ray Sicotte of Damascus.

Sicotte left the military work he was doing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to come to COMSAT in 1969, soon after

the laboratories opened. MIT scientists were at the core of COMSAT, but as the number of employees grew to more than 600, top

scientists and engineers from across the country and the world worked there.

The lab was sold to Lockheed Martin five years ago and most operations have since dissolved. Bethesda-based LCOR is the current

owner and wants to demolish the laboratory. Some are saying the COMSAT building should be deemed historic and saved. Many are

also saying the work that went on there was historic, as well.

"Those were the golden years," mused Ken Betaharon of Rockville, a COMSAT engineer from 1969 to 1978. "My first job out of

school ... [working with] state-of-the-art technology, ... cutting edge technology -- 37 years ago it was almost black

magic."

Bob Gruner of Damascus, who worked at COMSAT from the lab's opening until the mid-1990s, remembers working alongside the best

and the brightest from around the world.

Scientists and engineers from South America, India, Taiwan, Japan and other countries took two- or three-year sabbaticals from

their regular jobs to work at COMSAT, said Jack Singer of Germantown, a COMSAT technician from 1978 until the mid-1990s.

COMSAT Laboratories was the research and development arm of the Communications Satellite Corporation, created as a private

company by Congress in 1963 in response to President John F. Kennedy's challenge to establish a global communications

system.

"For a scientist and engineer, having a technical project with a budget was like being in a sandbox at the beach. We could

dream up solutions to problems and take the risks - quite a few came through," said Sicotte, who stayed at COMSAT for six

years. "At one time I said, 'I hope they don't realize how much fun we were having. They wouldn't want to pay us.' "

The United States launched COMSAT's first satellite, Early Bird (also called Intelsat I), in 1965. It could handle 240 phone

calls or one black and white television channel. It had a design life of 18 months. By contrast, Intelsat IV, launched in 1971,

could handle 4,000 telephone calls, color television and had a 7-year design life.

Some of the work done in microwave technology, solar cells, solid state systems, and semiconductors were found to have

widespread applications years after being developed at COMSAT.

The list of COMSAT Laboratories' accomplishments is extensive. Mike Onufry of Clarksburg knows of more than 300 patents

developed at COMSAT, including the nickel hydrogen battery. Onufry began work at COMSAT in 1966 and stayed for more than 25

years.

The nickel hydrogen battery provided a substantial improvement over the existing nickel cadmium battery. This resulted in an

increase in satellite battery lifetimes from five to seven years to the current 15-year life.

COMSAT got an Emmy award for developing small terminals for satellite newsgathering activities, Onufry said. The first

demonstration of satellite news gathering was in the mid-1970s.

Many former employees said COMSAT was a special place to work.

"People who came there were very much interested in the frontiers of science," Onufry said.

"When you woke up in the morning you were anxious to go to work," added Amin Ezzeddine of Germantown, who was recruited to work

at COMSAT when he graduated from MIT in 1982 and stayed for 12 years.

"If you were willing to learn, you could learn quite a bit," said Germantown;s Singer. "It was a wonderful environment of

intelligent people working on unique issues."

John Evans of Clarksburg was COMSAT's director from 1983 to 1996, a time that brought change.

"The lab was originally paid for out of the money collected from the Intelsat System," the company that launched the

intelligence satellites, Evans said. "Eventually Intelsat formed its own staff."

COMSAT was forced to seek its own funding and the character of the laboratories changed, he said. Many scientist left. Evans

estimates the staff dropped to around 230 during his tenure.

"People who stayed buckled down, and we were very successful," he said.

They seek to preserve the history of the accomplishments at COMSAT through the COMSAT Legacy Foundation, which is administered

by Steve Teller, a COMSAT engineer from 1982 to 2002.

"My goal is to help remember it for all the people who did that work," Teller said. He has hopes for a comprehensive history of

COMSAT and a documentary.

The foundation is arranging for the preservation of COMSAT materials formerly in the possession of Lockheed Martin and others

at the Johns Hopkins University library. The non-profit foundation is funded by contributions from COMSAT veterans. Former

COMSAT employees also formed an alumni association, called COMARA. Their last reunion was in December.

Information on COMSAT and the foundation is available on-line at

www.comsat-legacy.org

.